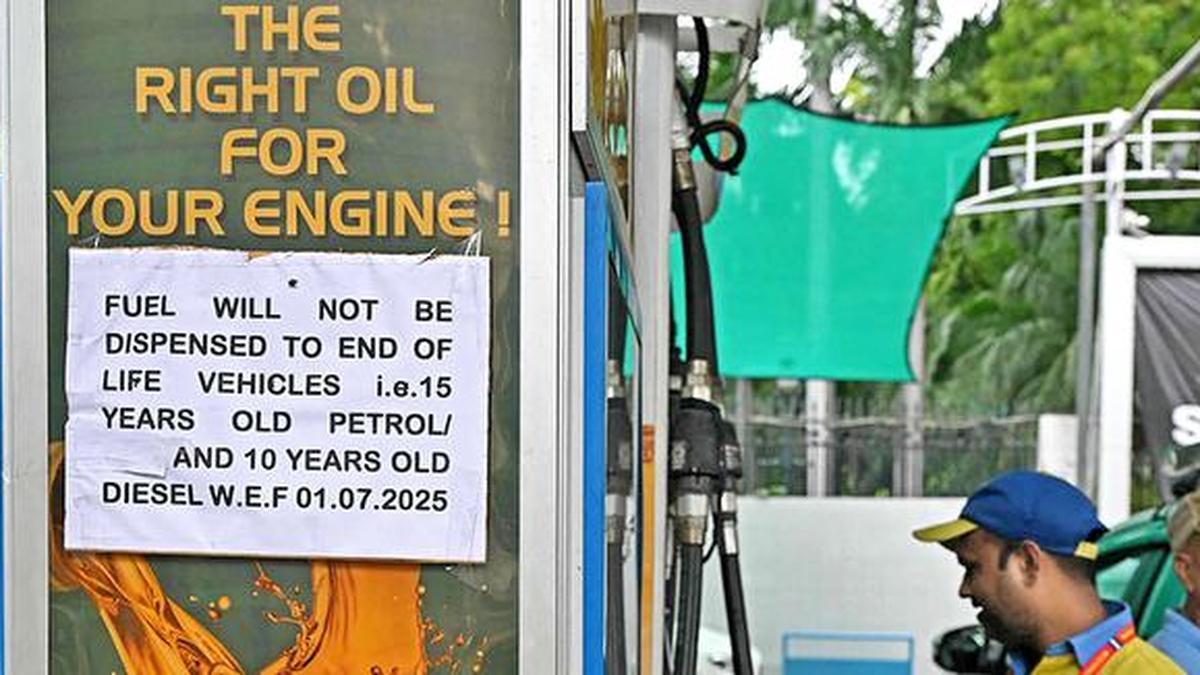

A notice announcing the fuel ban on overage vehicles displayed at a fuel station in New Delhi.

| Photo Credit: ARUN SANKAR

On July 1, 2025, Delhi launched a policy: petrol vehicles older than 15 years and diesel vehicles older than 10 years were no longer allowed to refuel at city petrol stations. Over 500 petrol stations were fitted with Automatic Number Plate Recognition (ANPR) cameras to identify non-compliant vehicles in real time. But implementation ran into trouble. Many ANPR systems could not accurately read high-security plates.

Fuel station staff lacked training, and there was no integrated blacklist to share vehicle status across agencies. Drivers refuelled in neighbouring towns just outside Delhi’s limits, bypassing enforcement.

The policy uses vehicle age as a proxy for emissions — simple to apply, but imprecise. Without fitness checks, odometer data, or emissions testing, age alone poorly reflects real-world pollution. Media reports have suggested that up to six million vehicles in Delhi might fall under the ban, but no official, disaggregated data exists. We don’t know how many are still on the road, what fuel they use, or how far they travel.

To independently assess the policy’s potential, we analysed vehicle registration records from the VAHAN portal for 2002 to 2025, covering all of Delhi’s Regional Transport Offices. We cross-referenced this with resale platform listings to estimate how many older vehicles are still active.

Travel survey data helped model typical daily distances by vehicle age. For pollution estimates, we used emission factors for particulate matter (PM2.5) from the Automotive Research Association of India, adjusted for Bharat Stage norms.

Our findings show that only 8% of Delhi’s current vehicle fleet (about 7.5 lakh vehicles) are covered by the fuel restriction (Chart 1).

This includes around 1.7 lakh two-wheelers, 3.5 lakh petrol cars, 1.8 lakh diesel cars, and 34,000 diesel commercial vehicles. Total PM2.5 emissions from Delhi’s transport sector in 2025 — including both tailpipe and non-tailpipe sources — are estimated at 3,200 tonnes. If fully enforced, the policy could reduce this by approximately 8% of total in boundary and transboundary vehicle movement emissions (Chart 2).

The projected impact is meaningful, but depends on sustained implementation. For a more sustainable solution, Delhi can learn from how other cities have tackled this challenge. Beijing paired diesel truck restrictions with scrappage incentives and retrofitting options. Tokyo enforced strict diesel standards while subsidising upgrades. Paris phased in low emission zones alongside public transit improvements and financial support for low-income users.

Delhi can also develop localised solutions. Vehicle exchange fairs, scrappage incentives, and legal interstate resale options could help owners retire older vehicles without hardship. Replacing the one-time lifetime road tax with annual conditional renewals would better align financial incentives with clean-air goals.

Public engagement is critical. A phased 12–18 month rollout with awareness campaigns would reduce confusion and build trust. A grievance portal could let citizens check compliance, contest errors, or seek exemptions.

Delhi should invest in scaling up environmentally sound scrappage centres and piloting retrofits like EV or hybrid kits. For small businesses, access to credit or vehicle replacement grants will be essential to avoid hardship.

Clean air doesn’t stop at city borders. Vehicles move across Delhi, Noida, Faridabad, Gurugram, and Ghaziabad. A joint enforcement task force and emissions tracking platform would help standardise efforts across the region.

Ajay S. Nagpure is urban systems scientist at the Urban Nexus Lab at Princeton University.

Published – July 11, 2025 07:00 am IST